Synopsis: The City of Boston has a multi-layered history, much like a palimpsest. With the proposed removal of an elevated highway (the Central Artery) cutting through the center of Boston’s historic neighborhoods, design solutions were solicited for how to transform the city and its newly configured urban topography. Traces of the Artery is a proposal that suggests that sections and fragments of the artery’s structure should be integrated into a newly evolving urban fabric, one where new, existing, and historic structures can become part of a larger urban collage.

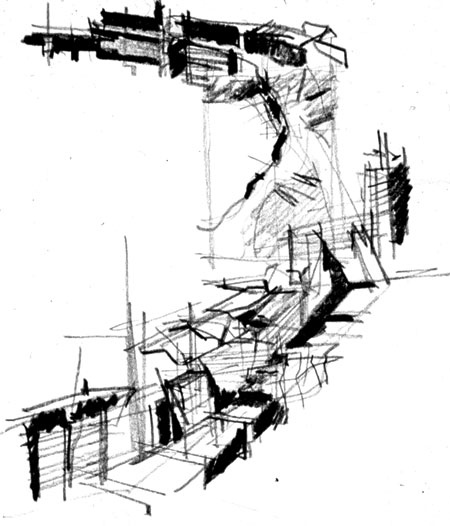

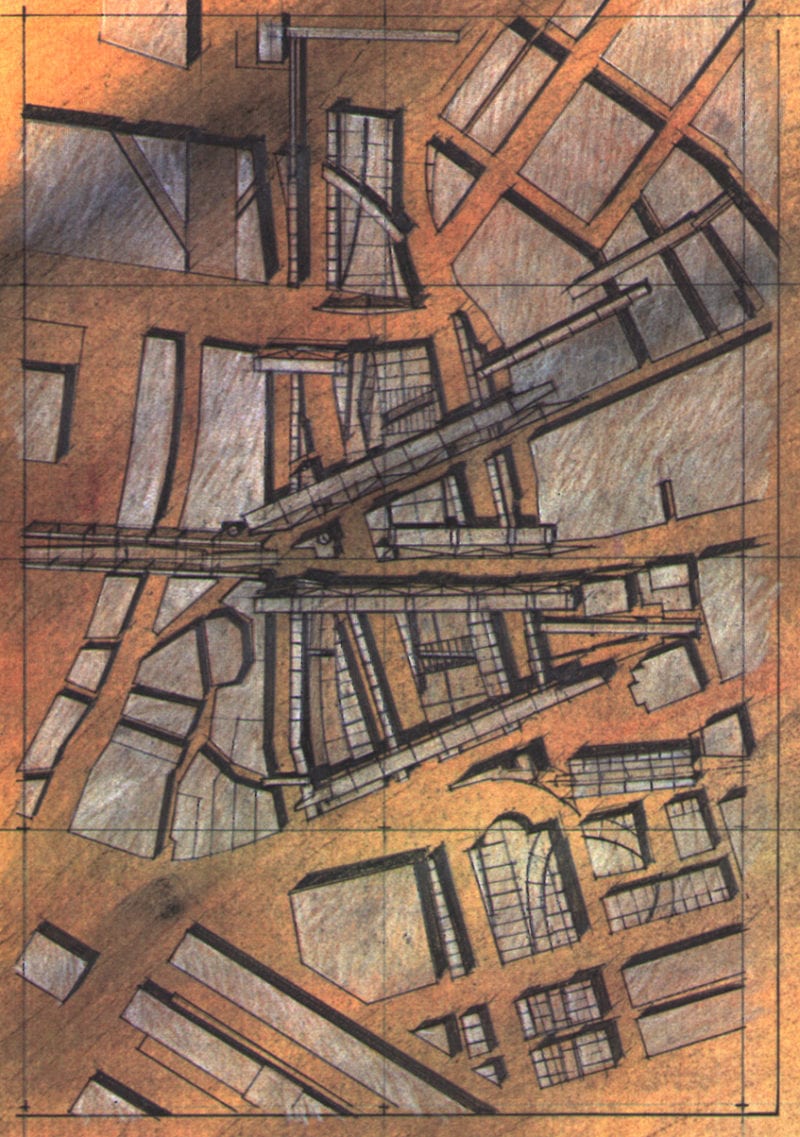

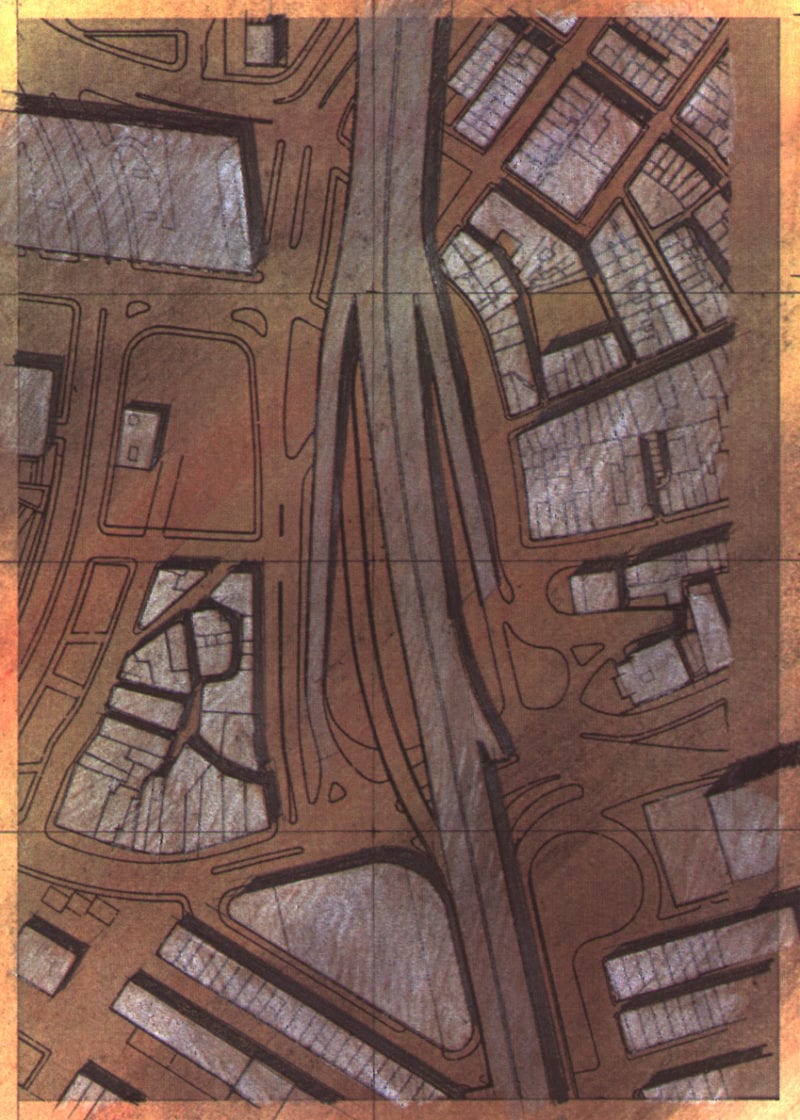

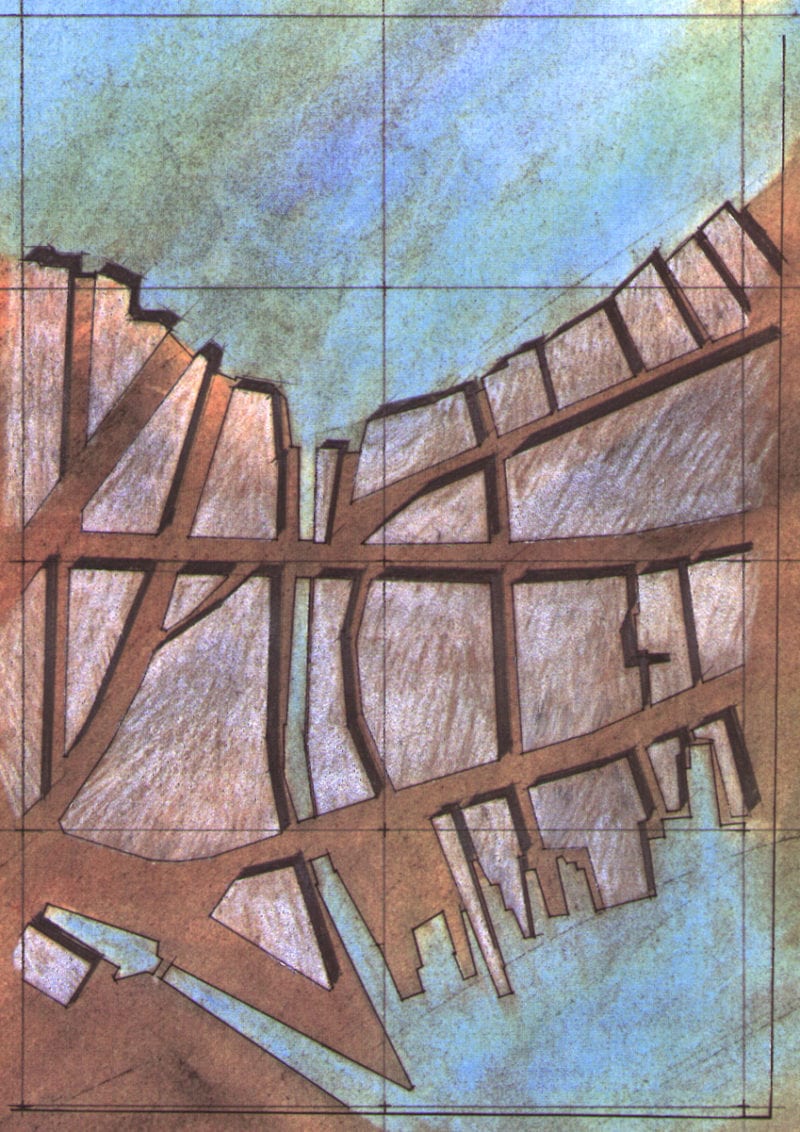

Numerous speculative studies and drawings were generated as part of an artistic and theoretical investigation into how city’s change over time, and how they might change in the future, based on a more nuanced understanding of a city’s underlying history and order. This proposal looks at time as an ally, where time and its residue help inform how urban places can be transformed in a way that generates a richer and more unique identity.

Detailed Description: In the 1980s, Boston’s downtown area, its waterfront, and adjacent neighborhoods faced potential monumental changes. You see, Boston’s urban rich history had evolved over 350 years, generating a multi-layered urban fabric that responded to Boston’s original topography, as well as societal and historical forces. This urban evolutionary process generated a unique city, unlike any city in the country. Despite the large evolutionary waves of incremental change over many centuries, massive and disruptive modifications still punctuated the city’s historic timeline.

For instance, a massive fire in the 1870s decimated much of the city’s central business district, prompting significant building and fire codes changes. In the 1950s, a similar enormous disruption to the city’s urban fabric took place when a multi-laned elevated highway cut through the center of Boston’s historic neighborhoods, severing urban connections between the waterfront and its adjacent neighborhoods and districts. Many buildings, streets, and plazas were erased from the city map, having a devastating impact on community members and the social and economic ties that bound them as a vibrant neighborhood. Boston’s North End and West End were, in particular, heavily impacted.

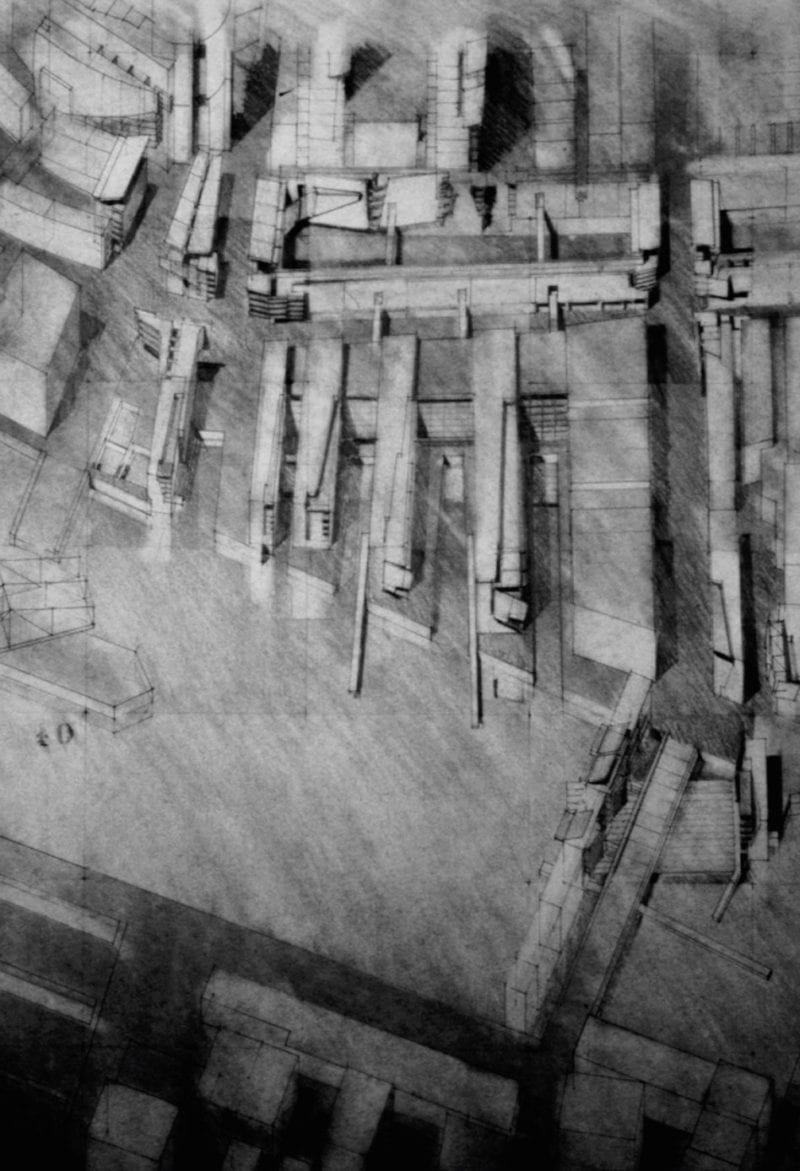

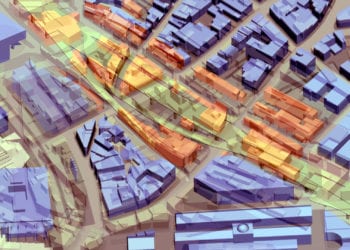

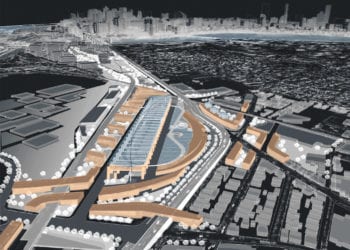

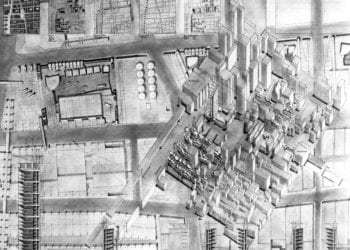

In the 1980s, new plans were developed and financed to heal the scar left by the Central Artery, the elevated highway. Innovative engineering solutions were developed to submerge the highway below grade, allowing a new tunnel to weave its way in between an underground network of subway lines, sewer lines, and other infrastructure systems. Immensely complicated, this project was slated to take over ten years to construct and several billions of dollars (ultimately over $15 billion). While the course of construction was certainly going to be disruptive to Boston’s daily civic life, the results and benefits were promising. In particular, over 27 acres of new land would become available for urban development to be inhabited by a new street network, public places/gardens, and buildings.

The question facing city planners and the community was: What will become of these 27 acres of potential development? What mix of uses might inhabit this newly developed land? What might it look like, and how would these new parcels of urbanity fit into the complex urban puzzle that is Central Boston? In collaboration with the city’s planning department, the BSA (Boston Society of Architects) sponsored an international competition (Boston Visions) with a call for ideas about this urban design challenge.

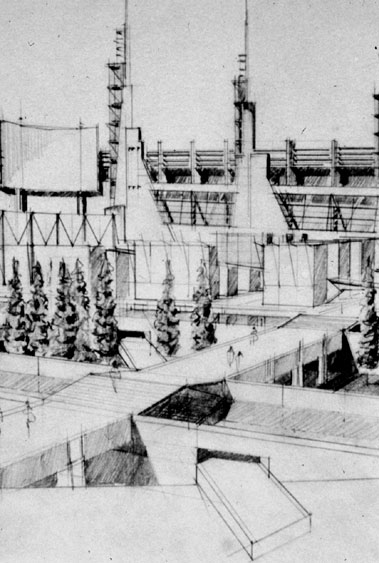

Traces of the Artery was the name of the award-winning entry submitted by Paul Lukez. The central idea was that a historic city like Boston could be thought of as a palimpsest. A palimpsest is a parchment that has been written upon and erased in successive layers over time, often leaving traces of past writings and erasures. The resultant parchment is a temporal collage – revealing multiple layers of time simultaneously. So too, the City of Boston and the proposed erasure of the Central Artery could leave numerous layers of development visible and legible to residents. Our proposal called for keeping parts of the Central Artery’s superstructure where it could be useful and re-purposed as part of new structures and spaces that might occupy the 27 acres of available land. These new structures would be composite structures, including both new constructions and older remnants of the Central Artery highway.

After the firm established in 1992, the design for this new district was re-visited. Numerous studies, drawings, collages, and models were generated. The images and studies became the basis for future professional and academic work. Professionally, this approach was utilized in the “North End Traces” project – a study done for the local North End community group. The drawings and studies also fed academic work, including course work, and later published a book, Suburban Transformations. And finally, the methodologies arising from these professional and academic work have since evolved and been integrated into PLA’s practice, particularly its urban design projects in China.